How the U.S. Failed to Contain COVID-19

In past viral outbreaks, the U.S. played a vital international leadership role. With a well-funded Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) and the ability to mobilize resources quickly, U.S. officials worked closely with scientists in Europe, China, and elsewhere, cooperated with allies, and followed the advice of scientists and epidemiologists. Today, in response to COVID19, the U.S. has done none of these things.

Much of the world has looked on in shock as the U.S. has cut off cooperation with scientists at the World Health Organization (WHO) and in China, alienated allies by trying to purchase exclusive rights to a vaccine from a German company, blocked a sale of masks to China, and undercut the guidance of public health officials and scientists.

The magnitude of the U.S. failure is difficult to overstate. Various states have adopted widely different strategies, although those states that refused to mandate masks, or who fully opened economies with no safety restrictions, are now reversing course as their hospitals fill with patients. The consequence is that cases in the U.S. – especially in the South – are spiking very sharply. Many states are at capacity for ICU units, while the number of infections is rapidly increasing.

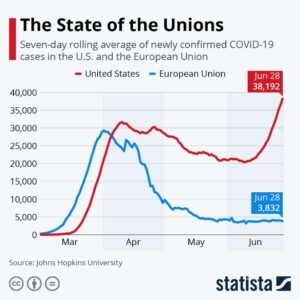

Meanwhile, new cases in the European Union (EU) have declined dramatically. On July 2, 2020, the U.S. recorded 57,236 new cases, whereas the EU reported around 3,450 – even though the EU has more than 100 million additional people. The small state of Arizona reported 3,333 new cases, despite having a population of less than 2% of the EU. The chart below shows the trends in the U.S. and the EU through late June, but the U.S. numbers have climbed rapidly since then, to well over 50,000 a day during the first week of July. Dr. Anthony Fauci, director of the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases, predicts that the U.S. will soon have 100,000 new cases a day.

Source: Statista, reference link: https://www.statista.com/chart/22102/daily-covid-19-cases-in-the-us-and-….

Why has the U.S. performed so poorly with COVID? The U.S. states have responded very differently to the virus, with some states imposing quick and comprehensive shutdowns of business and issuing shelter in place orders, and other states imposing minimal restrictions and rapidly opening their entire economy for business. So one possible explanation is the American federal system, which leaves states with substantial policy power to protect the health, safety, morals, and general welfare of their citizens. Federal systems have some important advantages compared to unitary political systems – states can experiment with policies, adapt policies to local conditions, and be flexible, but they also are not especially efficient in crafting a uniform national policy in response to a pandemic that quickly crosses state boundaries.

We have just completed a study of the early COVID responses of Australia, Canada, Germany, and the U.S. – four federal systems that vary on a number of factors. Australia is more centralized, with Canada and the U.S. more decentralized, Germany has a strong party system, and the U.S. a weak party system, and Australia and Germany are run by conservative governments, while Canada has a leftist government. Although Australia, Canada, and Germany differed somewhat in their responses to the virus, all three countries acted quickly, had substantial cooperation among the states, provinces, and Länder, and among political parties, and followed the recommendations of public health officials.

All three countries responded quickly with an economic stimulus plan that protected workers’ incomes and helped keep businesses afloat. The subnational governments differed somewhat in the details of their approaches but worked closely with national leaders and public health professionals. Partisan differences existed but were minor compared to what emerged in the U.S.

It is true that the U.S. has 50 states (plus the District of Columbia), compared with 16 Länder in Germany, six states and ten territories in Australia, and ten provinces and three territories in Canada. But in past health crises, the U.S. has performed far better than it has in 2020, and with far more unity.

The U.S. failure to mitigate the virus spread lies with the catastrophic performance of President Donald J. Trump, but also with the polarizing partisanship of which he is only the latest manifestation. That is, the political structures of the U.S. are well equipped to deal with this crisis, but the country’s leadership is not.

President Trump amused and horrified the world by first calling the virus a hoax, then promising it would go away soon, then talking of injecting disinfectants, and then promising again that the virus would just go away. Even in early July, with the number of cases growing exponentially in many states, the president has held rallies with tightly spaced crowds and most attendees not wearing masks. The image of the president without a mask and touring a factory that made testing equipment – making it necessary for the firm to destroy an entire day’s output – was widely commented on around the globe. One Italian journalist referred to President Trump’s approach to the virus as being “like a Mel Brooks film.”

In the three other federal systems, national leadership helped coordinate regional government responses, helped procure needed medical equipment, and created a national testing program. By coordinating equipment purchases at a national level, costs were low and needed supplies were quickly procured. In the U.S., the president told the states to go and get their own tests and equipment, and then frequently had the national government bidding against the states, which drove up prices. The national government then sometimes seized the materials that the states had purchased, redistributing along political lines. This led to one Republican governor, Larry Hogan of Maryland, holding the tests he had purchased from South Korea in an undisclosed location guarded by National Guard troops, protecting them against seizure by the national government.

When Democratic governors (along with some Republicans) ordered a shutdown of most businesses and for their citizens to shelter in place, Trump tweeted to his followers to liberate these states. Angry groups of white protestors, often heavily armed and in one case carrying Barbie dolls with hangman nooses as a threat to the state’s female governor, stormed state capitols, and in some cases blocked ambulances and shouted racist insults to doctors and nurses who stood in their way. Trump praised the protestors and urged governors to negotiate with them. When businesses opened in defiance of state edicts, Trump tweeted support.

Perhaps most importantly, Trump has consistently refused to wear a mask or to urge citizens to take the virus seriously. By July 4, Trump had been seen in public exactly once with a mask and had only occasionally advocated social distancing – not in a speech to the nation, but instead in answer to a reporter’s question. Many, but not all, Republican governors followed suit, generally issuing only minimal public health directives and then lifting them quickly. By July these states were the hardest hit with the virus, and Texas reversed course and reluctantly mandated that all citizens wear masks in public.

But Trump’s failures would not have done so much damage, had the Republican Party for many years not undercut the authority of the media, government officials, scientists, and public authorities. Whereas once the GOP was a party of reasoned conservatism, over time many of its most prominent leaders have undermined messages that conflict with their political agenda. This has allowed Trump to paint media accounts of the virus at first as a hoax and “fake news,” to paint government officials who worried about the virus as the “deep state,” and to undermine the scientists and public health officials who tried to warn of the virus and to call on citizens to wear masks. Hetherington and Ladd report that over time Republican voters have lost faith in media, government, and science so that in 2018, 65 percent had “hardly any” faith in the media, and only 39 percent had a great deal of faith in the scientific community. Small wonder that some of the protestors demanding that their states open up for business carried signs that read “Science is Fake News.”

Thus, the U.S. faces a wave of increasing infections, crowded emergency rooms, and ICU units near their maximum capacity in many states, and at the same time has protestors demanding the right to not wear masks and to gather together in crowded settings, at the same time that much of the rest of the world has endured the first wave of the virus and is cautiously opening up for more normal activities.

The failure of national leadership can be fixed with elections. Many congressional Republicans have refused to wear masks in Congress and made light of the virus, but as polling data increasingly showed a public that is very concerned, they are scrambling to appear responsible.

The angry polarization of American politics is more difficult to correct. Consultants, activists, and interest groups all profit from anger and fear of Americans toward one another. Russian troll farms create fake social media posts filled with fake stories of the depravity of one or another group of Americans. It will take a serious protracted effort by a range of American actors to reduce the polarization that has helped undermine the U.S. response to the virus.

Article by Mark J. Rozell, Dean of the Schar School of Policy and Government at George Mason University and Clyde Wilcox, Professor of Government at Georgetown University.

- Read more about the COVID Project here.

Further Reading:

Berry, Jeffrey M., and Sarah Sobieraj. The Outrage Industry: Public Opinion Media and the New Incivility. New York: Oxford University Press, 2013.

Rozell, Mark J., and Clyde Wilcox. Federalism: A Very Short Introduction. New York: Oxford University Press, 2019.

Rozell, Mark J., and Clyde Wilcox. “Federalism in a Time of Plague.” American Review of Public Administration (Forthcoming, 2020).