American Studies, Dialogue Series, Distingushed Lectures, Regional Studies

Mehran Kamrava International Lecture

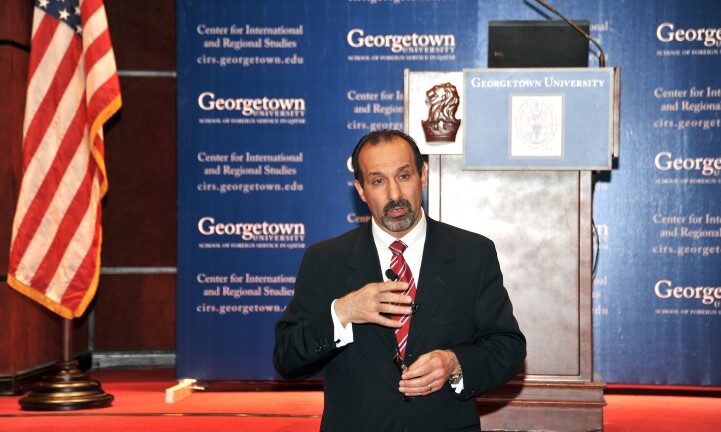

Georgetown University School of Foreign Service in Qatar, Dean Mehran Kamrava speaks about “A 2020 vision of the Middle East”

Click here to download an MP3 of Kamrava’s speech

In its inaugural International Lecture, CIRS travelled to the Kingdom of Bahrain on April 26, 2010, to offer insights and dialogue with people in the neighboring GCC state. In this unique Public Affairs Program, CIRS emphasized the objective of providing a forum for exchange of ideas with other communities in the Gulf region and beyond. The distinguished speaker, Mehran Kamrava, was introduced to the audience by GU-Qatar Alumna Haya Al Noaimi.

Kamrava is Interim Dean of the Georgetown University School of Foreign Service and Director of the Center for International and Regional Studies. He lectured on the topic of “A 2020 Vision of the Middle East,” where he introduced and analyzed several key trends he sees that have the ability to shape the future of the Middle East over the next ten years. Kamrava said that, “as students of the Middle East, and as citizens of the region, often times we dwell on the past.”

Outlining the evening’s lecture, the four primary areas that Kamrava focused on were related to 1) the nature of the state that currently exists across the Middle East; 2) the role and the nature of the relationship between the United States and the region; 3) the Israeli-Palestinian conflict; and 4) trends occurring in the Gulf region, including the events unfolding in Iran and Iraq.

Turning to the first area of discussion, or “the state of the state” in the Middle East, Kamrava argued that there are a number of different political dynamics that are currently being played out in the international arena. There are a number of different state formations and governance models that range between the democratic, the non-democratic, and the many other models in between these two opposing spectrums. In the Middle East, there are democratic models of governance that vary in their viability and vibrancy; “some democracies are somewhat more cosmetic, or at least have much more limited political parameters around them – you might call them pseudo democracies,” of which Turkey, Israel, and Lebanon are good examples, Kamrava said.

The Middle East also has several states that are non-democratic as they attempt to exclude the public from any political participation through the instrumentalization of repressive mechanisms. There are other political systems in the region that are thoroughly non-democratic, but try to appear democratic. Many of these non-democracies, Kamrava argued, “try to be inclusionary and inclusive insofar as the population is concerned – the streets become democratic theaters.”

Discussing the United States’ relationship to the region, Kamrava argued that since WWII, there have been four primary features that have guided American foreign policy towards the Middle East. These include, guaranteeing the safety and security of the state of Israel; guaranteeing access to Middle Eastern oil at reasonable prices; containing regional threats to American interests across the region; and, “after the Cold War – or once Iraq invaded Kuwait – there was a fourth aspect and that was to station military forces in the region directly because regional allies, at least insofar as the United States saw them, turned out to be unreliable for American policy calculations,” Kamrava argued. Expounding upon American military presence in the Middle East, he said that if one looks at a map, it becomes clear that “across the Middle East, there is a very strong American presence” in the form of large and easy to mobilize military bases. To this effect, Kamrava said, “the big question is: does it look like, at any time in the foreseeable future, even in the next ten years, the American military is going to disengage from the Middle East?”

These features of American foreign policy, Kamrava said, are instrumental to the third area of discussion regarding the Israeli-Palestinian conflict. “America’s alliance with Israel is certainly key in the way that the Israeli-Palestinian conflict has unfolded historically and also currently,” he said. Projecting his views on the situation, Kamrava said that “as we move forward, we can see a continuation of this unending ‘peace process,’” especially in light of the encroachment of illegal Israeli settlements and rapidly increasing population growth. With this knowledge in mind, and by looking at the sobering facts on the ground, he posed an uncomfortable question to the audience by asking “does it still make sense to talk about a Palestine?”

Looking into the future, Kamrava posed three possible models for what future political turns Palestine might take. The first of these is the “Tibetan model,” where Palestine’s objective to be an officially recognized sovereign state all but disappears as it becomes subsumed under Israel. In this model, “although there is a Palestinian identity, there will not be a Palestinian state,” Kamrava explained. The second and opposite possibility is for Palestine to take on the “East European” or “Central Asian” model, which is for it to emerge as a distinct state in the future. The third, and final, model is for Palestine to become a disparate amalgam of reservations and entities that are landlocked and isolated from one another with little economic and political power.

Finally, turning to the Gulf region, Kamrava projected that, politically, “I don’t think much is going to change, at least insofar as states are concerned” in the GCC, but it is very difficult to predict what will happen in Iran over the next few years. He added that “the regional superpowers [Iran, Saudi Arabia, and Egypt] are not going to be as dominant in dictating regional foreign policy.” Indeed, “we will see a continued ascendance in the economics of the Gulf region, particularly smaller countries like Bahrain and Qatar.” The region will see a new set of powers that, because of their economic wealth, policy agility, and elite cohesion, will become more prominent in shaping the future of the GCC, the Middle East, and beyond.

In conclusion, Kamrava summed up his prognosis for the Middle East of 2020 by saying that “what we will continue to see in the region are American ‘footprints,’” in the form of U.S. military bases, as well as “a continued domination of Israel.” He also noted that “I don’t think there is going to be a wave of democracy sweeping across the region and that is because oil-based economies will continue to exist throughout the region.” As a final thought, Kamrava said that he was optimistic that we will see “the continued enrichment of human capacity and human capital in every country of the Middle East.”

Dr. Mehran Kamrava is Interim Dean of the Georgetown University School of Foreign Service in Qatar and Director of Georgetown’s Center for International and Regional Studies. He is an expert in comparative politics, political development, and Middle Eastern politics. He is the author of nine books, including, most recently, Iran’s Intellectual Revolution and The Modern Middle East: A Political History Since the First World War.

Article by Suzi Mirgani. Mirgani is the CIRS Publications Coordinator.